Upper endoscopy

This test looks at the inside of the upper part of your digestive system. This includes the gullet (oesophagus), stomach and the first part of the small bowel.

What is an upper endoscopy?

An upper endoscopy is a test to look at the lining of the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum (the first part of the small bowel). It is also called an upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy. This test can help diagnose cancer.

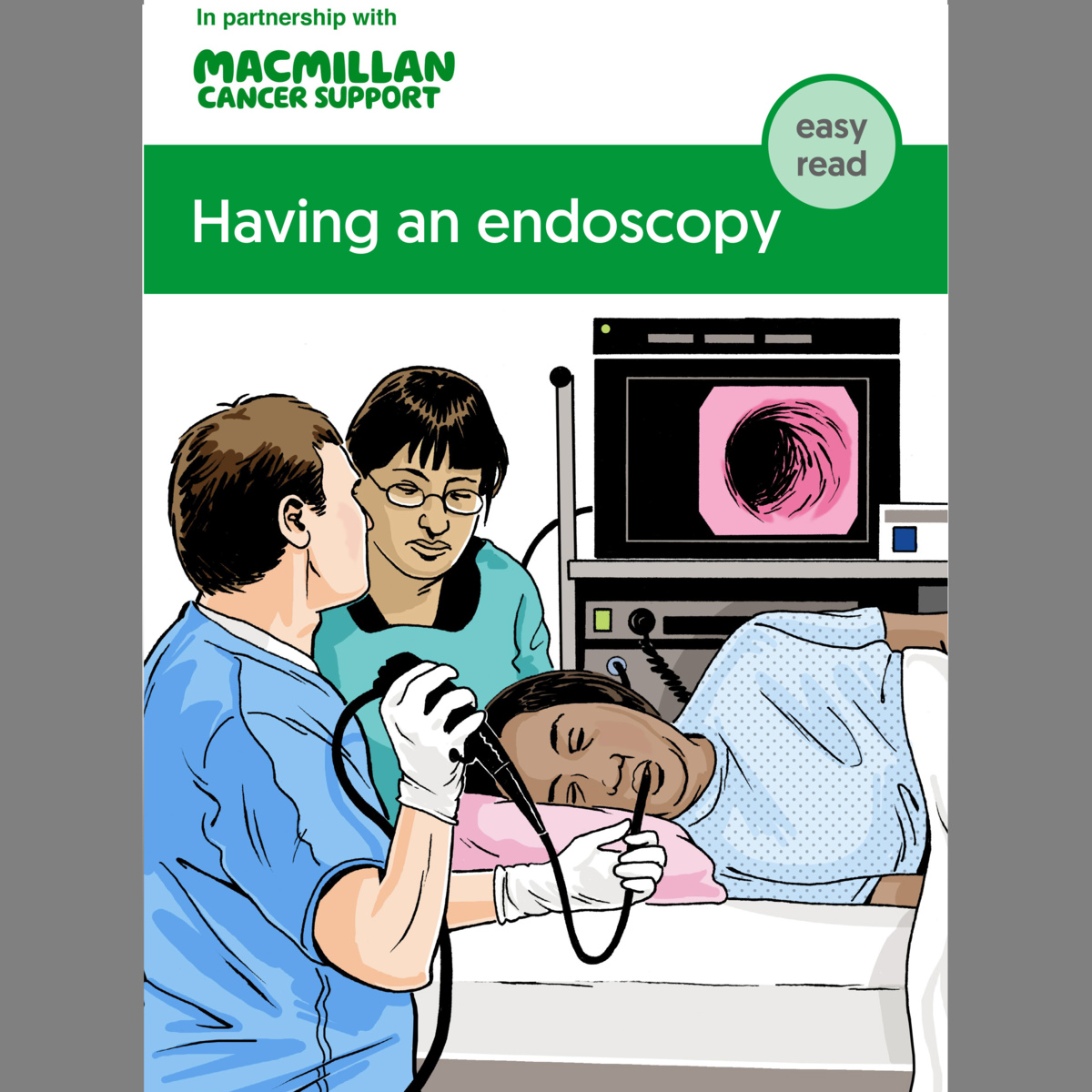

A doctor or specialist nurse uses a thin, flexible tube with a light and camera at the end. This is called an endoscope. It helps them see any abnormal areas.

Stomach endoscopy

This test may have other names depending on the area examined:

- A gastroscopy or gastrointestinal endoscopy looks inside the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum (the first part of the small bowel). This is also called an oesophago-gastroduodenoscopy or OGD.

- an enteroscopy looks further into the small bowel to the jejunum and ileum.

Related pages

Booklets and resources

Having an upper endoscopy

You usually have an upper endoscopy as an outpatient, so you can go home the same day. Your doctor or nurse will ask you not to eat or drink anything for several hours before the test. They will also give you instructions about any medicines you are taking.

An endoscopy takes about 10 minutes, but you may be in the hospital for a few hours.

During the test

When you have the endoscopy, you lie on your side on a couch. The doctor or nurse may spray a local anaesthetic on to the back of your throat. This makes it numb, so you do not feel anything during the test. Or they may give you a sedative to make you feel drowsy. They inject the sedative into a vein in your arm. You may have both the injection and the spray.

The doctor or nurse then passes the endoscope through your mouth and throat, down the oesophagus and into the stomach. During the endoscopy, they may remove small samples of tissue from any areas that look abnormal. This is called a biopsy.

When the test has finished, the doctor or nurse will gently remove the endoscope.

An endoscopy can be uncomfortable, but it should not be painful. If you have any chest pain during or after the test, tell the doctor or nurse straight away.

After an upper endoscopy

If you have had a biopsy, a doctor in a laboratory will look at the tissue under a microscope. This is to check for any changes to cells.

If you have had a sedative, the effects should only last a few hours. You should not drive after having a sedative. You will need to ask someone to drive you home or travel home with you.

If you have had an anaesthetic spray, you will need to wait until your throat stops feeling numb before you eat or drink.

You may have a sore throat after the endoscopy. This is normal and should get better after a few days.

Related pages

About our information

This information has been written, revised and edited by Macmillan Cancer Support’s Cancer Information Development team. It has been reviewed by expert medical and health professionals and people living with cancer.

-

References

Below is a sample of the sources used in our small bowel cancer information. If you would like more information about the sources we use, please contact us at informationproductionteam@macmillan.org.uk

AB Benson, AP Venook, MM Al-Hawary et al. Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma, Version 1.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 17(9), 1109-1133. Available from: www.jnccn.org [accessed January 2023].

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Wireless capsule endoscopy for investigation of the small bowel. Published: 15 December 2004. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg101 [accessed January 2023].

Date reviewed

Our cancer information meets the PIF TICK quality mark.

This means it is easy to use, up-to-date and based on the latest evidence. Learn more about how we produce our information.

The language we use

We want everyone affected by cancer to feel our information is written for them.

We want our information to be as clear as possible. To do this, we try to:

- use plain English

- explain medical words

- use short sentences

- use illustrations to explain text

- structure the information clearly

- make sure important points are clear.

We use gender-inclusive language and talk to our readers as ‘you’ so that everyone feels included. Where clinically necessary we use the terms ‘men’ and ‘women’ or ‘male’ and ‘female’. For example, we do so when talking about parts of the body or mentioning statistics or research about who is affected.

You can read more about how we produce our information here.